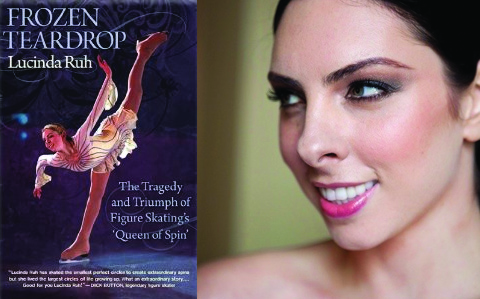

I was contacted out of the blue by Lucinda Ruh to be interviewed for the skatecast. Imagine my glee at finding that email in my inbox! Of course I was thrilled. She graciously sent me an advance copy of her new book “Frozen Teardrop: The Triumph and Tragedy of Figure Skating’s Queen of Spin” which was released in the USA on November 15th, 2011. In her podcast interview we discuss the book at length.

While the book is 243 pages long in paperback, it’s a fascinating and fast read. She chronicles her life starting before she was born and up through her career-ending injuries, and it’s a remarkable tale of courage, pain, tenacity and redemption. For those of us who watched her skate and grow up before our eyes in competition after competition, the tales she tells of her training schedules and conditions will shock you. I was brought to tears several times. Little did those of us watching her elegance and creativity on the ice know what she had to endure for her art.

It is well-known that Lucinda was truly a global skater: born Swiss, but raised and trained in Paris, Japan, Canada, China, and the USA. Initially she trained for years as the lone westerner in Japan. Her auspicious start begins with revered coach Nabuo Sato (father of Yuka Sato) telling her as a very young child of just seven years old, that if he wants her to train with him she must come to the rink every day for six months before he will even consider giving her 20 minutes of his time each week. And here is where Lucinda first develops her fierce determination, because she actually does it and earns Sato as a coach. As she and her mother are isolated by geography and culture, they turn to each other for support and her mother does her best to raise an extraordinary child in extraordinary circumstances with no role model to follow or local support system. Lucinda endures bullying by peers for being the sole westerner, and eventually severe beatings by her own mother as her talent becomes evident and the desire to succeed becomes all-encompassing.

Eventually Lucinda must switch coaches after Sato feels he cannot develop her talent any further, and Lucinda make some rash decisions to head west. A few short stints switching coaches and not finding a right fit, she finds the perfect coach back East as she travels to China. Again as the sole westerner under shocking working conditions (any skater that thinks their training conditions are tough have nothing on Ruh), her talent thrives, only to be taken away from her as the Chinese Federation interferes with her coaching arrangement. Lucinda and her mother continually lean on each other to an unhealthy degree, as they have nobody else to support them. Even the Swiss Federation never considers Lucinda as one of their own since she never trained in Switzerland, and they choose to waste the opportunity to send Lucinda to the 1998 Olympics and let the spot go unused.

Where she found solace was when she was spinning. Fans will be surprised to know that she is self-taught in spins (so much for the theory that the Swiss coaches produce the best spinners). Her father tells her that he will be proud of her if she can find one thing that she does better than anyone in the world, and as we all have witnessed she surpassed that goal by miles. How equally tragic that she is no longer able to spin since she was diagnosed with brain damage caused by the very spins that gave her peace. Both she and fans have been robbed of her extraordinary gift, as none of us will see her perform these spins again, and we are thankful for many videos of past performances that we can watch as a reminder of her remarkable spinning ability.

Ultimately Lucinda’s body breaks own slowly over the years, as injuries from skating, beatings, eating disorders, and the slow onset of concussions in her brain take their toll. Despite all this, the reader finishes the book feeling uplifted. This is due to Lucinda’s incredible ability to see the positive in everything, and her amazing gift of forgiveness. Her relationship with her mother is made stronger by the experience (her mother writes the afterword of the book) and she walks away with few regrets from a sport that took her body but never dampened her spirit. As an armchair psychologist with no training at all in how victims’ minds operate, I have to wonder if Lucinda suffers a bit from the Stockholm Syndrome, as she defends her mother’s actions throughout the book.

Lucinda Ruh made spins important. I would argue (and I can expect many will agree) that while Lucinda was at her physical best well before the International Judging System came to replace the old 6.0 system, her spins are the benchmark set by the ISU by which all other skaters today are ranked in the quality of their spinning ability. How I wish we could have seen a Lucinda Ruh spin marked under COP!

What really struck me as an untold story of the book was her acceptance rather than condemnation of the Japanese coaching system. Lucinda tells of students being regularly beaten when they didn’t perform well. Why have none of us (or myself, if I’m the last to know) heard this before? With the recent rise of the Japanese skaters in the past 10 years, it makes me wonder if the tactics were abandoned or are still in use to produce such recent success in both the Men’s and Women’s fields. And yet while she was beaten, pushed, drilled and generally worked to the edge, she seems to almost yearn for the body-breaking discipline once she moved west to train in North America.

All the more remarkable is that while English isn’t her first language, the book is almost perfectly written in English with only a very few odd phrases or grammatical errors scattered throughout. In the past when budgets in the publishing industry were larger, I’d assume a proofreader was involved. But these days you can never be assured of that. After speaking with her on the phone, her near-flawless command of the English language made me realize that she did it all herself. I just respect her more and more!

I highly recommend this book to all skating fans so they can be inspired by Lucinda’s story. We can all only hope that we can learn to overcome our adversities with similar grace and forgiveness. While we can no longer have the pleasure of watching her perform live, all skating fans are enriched by how she changed the sport for the better. As Dick Button once quipped, “Good for you, Lucinda Ruh!”

Some performances via YouTube:

1999 Worlds Short Program: “Lawrence of Arabia”

1999 Worlds Long Program

2000 World Pros: Artistic Program “Mercy Prayer Cycle”

2001 Star Skates “Blues for Klook”